Let's Be Tolerant

26 March 2006

A poster you could see around Brno not too long ago:

Make of it what you will. Thank goodness so many people remember that no one opposed the entry of the Czech Republic into the EU, less than two years ago. No one was upset by that, were they? (Oh wait, then complaints were by the Irish and about mad cow disease, cheap labor from the East, and economic instability. Now the Czechs et al. fear the Turkish, bird flu, and Eastern (in these parts, i.e., Ukrainians) workforces flooding the labor market. A completely new set of arguments.)

Tagged: Czech, Brno, Europe, EU

European Petition

Against the entry of

Turkey

into the EU

You can sign the petition here:

Brno, náměstí Svobody [i.e., "Freedom" or "Liberty" square]

everday after 30 May 2005

10.00 - 16.00

On-line petition:

www.hlasproevropu.org

Let's Be Tolerant, Not Naive

Make of it what you will. Thank goodness so many people remember that no one opposed the entry of the Czech Republic into the EU, less than two years ago. No one was upset by that, were they? (Oh wait, then complaints were by the Irish and about mad cow disease, cheap labor from the East, and economic instability. Now the Czechs et al. fear the Turkish, bird flu, and Eastern (in these parts, i.e., Ukrainians) workforces flooding the labor market. A completely new set of arguments.)

Tagged: Czech, Brno, Europe, EU

You too can fly to Brno ...

25 March 2006 ...if you flap your wings hard enough and long enough, you may eventually end up at Tuřany, Brno's International Airport. It happened to me, in fact.

...if you flap your wings hard enough and long enough, you may eventually end up at Tuřany, Brno's International Airport. It happened to me, in fact.I visited the Brno airport for the first time ever today. Though rather disappointing as a destination, I did get to ride an overcrowded bus, see yet another bus stop in the middle of a field, and witness many Czechs reunited with family members who returned in kilts, bomber hats, and other paraphenalia. One person even brought a trombone! (I claim no affiliation with said instrument, but I was glad to note it arrived.)

It was hard to tell from the crowd, but this was the first flight of the second year of service to Brno by Ryanair. March 24 marked the one-year anniversary of daily service between London (Stansted) and Brno (Tuřany - yes, of course there's more than one airport in Brno). Moderní Brno reports:

Brno - A roll of the drums, a cimbalom band, the Minister of Transportation, girls in kroj, pastries, and slivovice - this was exactly how the arrival of the first airplane of the regular Brno-London route was celebrated. "The route to London should bring more than 100,000 passangers to the airport per year," predicted then-optimistic minister of transportation Milan Šimonovský. The number of passengers exceeded the minister's prediction after a year of service. "After a year of operations in Brno we sold over 140,000 seats and served 115,000 travelers," stated Tomasz Kulakowski, sales and marketing manager for Ryanair's Central Europe division. The difference in numbers was created by passengers who bought tickets and never used them.

Brno - Víření bubnů, cimbálovka, ministr dopravy, krojované dívky, koláčky a slivovice - tak se přesně před rokem slavil přílet prvního letadla pravidelné letecké linky Brno-Londýn. "Linka do Londýna by měla přinést letišti navíc sto tisíc pasažérů za rok," předpovídal tehdy optimisticky ministr dopravy Milan Šimonovský. Počet přepravených pasažérů po ročním provozu dokonce překonal ministrovo očekávání. "Za rok našeho působení v Brně jsme prodali 140 tisíc míst a přepravili 115 tisíc cestujících," konstatoval Tomasz Kulakowski, manažer prodeje a marketingu společnosti Ryanair pro střední Evropu. Rozdíl mezi oběma čísly tvoří letenky, které si pasažéři koupili, ale nakonec je nevyužili.

The Prague Post ran a story back in March 2005. RyanAir's Caroline Baldwin had this to say at the time: "There will be a huge upsurge of interest in Brno. . . . Prague is over in the UK. Been there, done that." It does seem that some British tourists just hop on the plane without knowing much about their destination. One bus rider who noticed me speaking English asked, "So, what is there to do in this town?" "Well...there's always the Zetor tractor factory," I answered, "My friend Stanley has been doing research on Czech economics and says that the factory has fallen on hard times so I'm sure they'd offer a tour for a small fee." So I'm actually making up the subject of that conversation, but it really did take place and I hope that he and his mates found something.

The Prague Post ran a story back in March 2005. RyanAir's Caroline Baldwin had this to say at the time: "There will be a huge upsurge of interest in Brno. . . . Prague is over in the UK. Been there, done that." It does seem that some British tourists just hop on the plane without knowing much about their destination. One bus rider who noticed me speaking English asked, "So, what is there to do in this town?" "Well...there's always the Zetor tractor factory," I answered, "My friend Stanley has been doing research on Czech economics and says that the factory has fallen on hard times so I'm sure they'd offer a tour for a small fee." So I'm actually making up the subject of that conversation, but it really did take place and I hope that he and his mates found something.It was not just the anniversary that attracted my attention. Just in case you missed it, a cimbalom band was playing at the inauguration of this service! If only I could have been there with my MiniDV to document it.

A picture from bus 76 to the airport. Evidence of foreign investment south of Brno, or an ad for South Moravian weather by CzechTourism?

Tagged: Brno, transportation, milestones

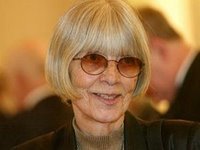

Jaroslava Moserová

Jaroslava Moserová died on Friday morning after a long fight with cancer. Moserová was known as a senator, translator, writer, and doctor. She was 76. Though not as well known as ex-President Havel, Moserová was one of those quiet fighters with strongly held principles and, I think, was one of the most admirable and admired figures on the recent Czech political scene.

Jaroslava Moserová died on Friday morning after a long fight with cancer. Moserová was known as a senator, translator, writer, and doctor. She was 76. Though not as well known as ex-President Havel, Moserová was one of those quiet fighters with strongly held principles and, I think, was one of the most admirable and admired figures on the recent Czech political scene.I saw Moserová during a visit to (of all places) Spillville, Iowa, in 2003. She was a person full of energy, life, and curiosity. During a tour of the Saint Wenceslas Church she insisted on being shown the organ loft and played the opening of Bach's Tocatta and Fugue in D Minor. The town is famous for hosting composer Antonín Dvořák who stayed there during his trip to the U.S., and that organ was possibly the same that he played most mornings during his summer in Spillville.

I also remember translating a portion of her memoirs for a Czech exam. In the section we translated, at least as I vaguely remember it, she described an unknown boy who turned up at her family's apartment. The boy turned out to be Miloš Forman, a Czech film director still active in the United States. (Forman directed the film version of Hair and many other better-known films, although I like his early Czech New Wave films from the 1960s like Lásky jedné plavovlásky ["Loves of a Blonde"].)

In her career as a burn specialist, Moserová was the first doctor to treat Jan Palach after his self-immolation act on Wenceslas Square (Prague) in January 1969. She said, "I heard the news when he was actually brought in. And as you know I don't like to talk about it. He was fully conscious and he could talk. The first day he could still talk without great difficulty. And he kept repeating 'tell everyone why I did it' and we did try to tell everyone. And we kept telling him, that what he did was not in vain. It was highly oppressive, the whole situation. The fact that people that were not only giving up but also giving in, and the slow demoralisation was setting in. And that's why he did it - he didn't do it because of the occupation, but because of the demoralisation that was setting in. He wanted to shake the conscience of the nation. And he did - not only in our country, in many others as well."

Rob Cameron of Czech Radio recalls meeting her: "Jaroslava Moserova made a deep impression on all who met her, not least inexperienced radio reporters taking their first tentative steps into journalism. When I first met her she was standing as an outsider in the 2003 presidential campaign - a female David standing up to two political Goliaths. She beat the first - Milos Zeman - only to be eradicated by the second, Vaclav Klaus. But while she was diminutive in stature she was, for many people, a towering moral authority."

During the 1990s she served as the Czech ambassador to Australia and New Zealand. She also served in various functions with the Czech and Executive UNESCO boards. Upon receiving an order of merit from French President Jacques Chirac in 2004, she wrote (my translation): "My credo has always been to do that which you have to do, to do it as best you can, and not to lie, at least not to oneself. Of course I have lied about a few things, but only for the loftiest of reasons in this or that. To this day I can only remember two times when I lied consciously in answer to a direct question, and I will never be able to forget them. During the times of darkness I did not display heroism, but I didn't sell out either."

Further:

Czech Radio tribute by Rob Cameron

Czech Radio mention

Moserová's Web site

Lidové noviny obituary (in Czech)

Photo by Tomáš Krist (Lidové noviny), 2003.

Tagged: Czech, people, culture, Moserova

Watch Your Step

24 March 2006

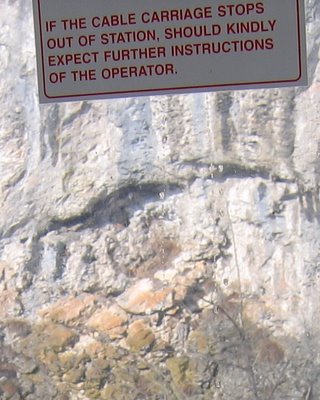

Late last year the Czech Republic adopted a new smoking law. It allowed restaurants to provide a smoking section during lunchtime (it was previously against regulations to smoke in a restaurant during lunch), and it prohibited smoking at tram stops. Apparently the reasoning was that 1) you were eating unhealthy food anyway and 2) the tram stops were dirty. I just hope no one tries to start a tramside restaurant.

As you might imagine, many people ignore the new regulations and smoke at tram stops anyway. (I actually saw someone ticketed one evening for smoking at the tram stop! It was dark and the police just pulled up behind me, and I thought, "Uh oh. I don't have my passport. How did they know?" Then one of the cops got out and gave the guy standing next to me a ticket for smoking.) I can't say that the tram stops seem much cleaner overall.

It seems to me that public parks could use some help, too. Often the smaller ones are not just dirty, but also full of muddy paths, broken park benches, and evidence of dogs. Some also have litter problems since trash cans can be scarce - it depends on the park. I saw the above sign outside a park in Jindřichův Hradec, a town in Eastern Bohemia. It notifies viewers, "Walking Dogs Is Prohibited," although I think the graphic shows the real problem. The problem, I suspect, is not the dogs, but the people who don't pick up after them.

So here's an idea for Czech planners. First, get more of these signs. Then, develop something similar to put at tram stops. Or perhaps they could develop a mascot like Woodsy Owl - "Give a hoot and don't pollute." Perhaps a Scotty dog for the park? Then come up with a better slogan: "Bring a mitt, pick up that ..." A similar campaign could be adopted for the tram stops. The possibilities are endless...

Tagged: Czech, signs, cleanliness

As you might imagine, many people ignore the new regulations and smoke at tram stops anyway. (I actually saw someone ticketed one evening for smoking at the tram stop! It was dark and the police just pulled up behind me, and I thought, "Uh oh. I don't have my passport. How did they know?" Then one of the cops got out and gave the guy standing next to me a ticket for smoking.) I can't say that the tram stops seem much cleaner overall.

It seems to me that public parks could use some help, too. Often the smaller ones are not just dirty, but also full of muddy paths, broken park benches, and evidence of dogs. Some also have litter problems since trash cans can be scarce - it depends on the park. I saw the above sign outside a park in Jindřichův Hradec, a town in Eastern Bohemia. It notifies viewers, "Walking Dogs Is Prohibited," although I think the graphic shows the real problem. The problem, I suspect, is not the dogs, but the people who don't pick up after them.

So here's an idea for Czech planners. First, get more of these signs. Then, develop something similar to put at tram stops. Or perhaps they could develop a mascot like Woodsy Owl - "Give a hoot and don't pollute." Perhaps a Scotty dog for the park? Then come up with a better slogan: "Bring a mitt, pick up that ..." A similar campaign could be adopted for the tram stops. The possibilities are endless...

Tagged: Czech, signs, cleanliness

Expozice nové hudby

23 March 2006 Brno is not a famous destination for fans of new music. The city does, however, host a few annual music festivals, and among these is the New Music Exhibition (Expozice nové hudby). This year’s 19th annual exhibition, titled Cestou odebírání (The Journey of Reduction) featured "alternative" minimalisms. The festival organizers stated that, while some music intends to expand expressive materials, a lot of other music tries to restrict them, perhaps in a stoic or ascetic act of cleansing. These are minimalisms that do not focus on rhythmic loops and displacement like Steve Reich and Philip Glass; instead, they focus on music that isolates individual musical elements like pitch and timbre. The listener, aided in thus isolating said elements, is able to contemplate them until his or her perception transcends the cultural desensitization and selective hearing that we all learn throughout the course of our lives. The intent is to re-experience said elements anew, as if from a child’s perspective. Well, it sounds "interesting" in theory.

Brno is not a famous destination for fans of new music. The city does, however, host a few annual music festivals, and among these is the New Music Exhibition (Expozice nové hudby). This year’s 19th annual exhibition, titled Cestou odebírání (The Journey of Reduction) featured "alternative" minimalisms. The festival organizers stated that, while some music intends to expand expressive materials, a lot of other music tries to restrict them, perhaps in a stoic or ascetic act of cleansing. These are minimalisms that do not focus on rhythmic loops and displacement like Steve Reich and Philip Glass; instead, they focus on music that isolates individual musical elements like pitch and timbre. The listener, aided in thus isolating said elements, is able to contemplate them until his or her perception transcends the cultural desensitization and selective hearing that we all learn throughout the course of our lives. The intent is to re-experience said elements anew, as if from a child’s perspective. Well, it sounds "interesting" in theory.This kind of music can try your patience. During Wednesday night’s performance of works by Alvin Luciera, no less than three audience members left during the riveting Still and Moving Lines of Silence in Families of Hyprebolas for solo cello and laptop (it was a PowerBook). They probably couldn’t take the excitement. Of course, the entire evening was marred by technical difficulties. This resulted in annoying buzzes from the speakers and goaded the technicians, perhaps in the hopes of fixing these problems, to turn the lights off and on in a whimsical fashion. The composer’s blurted "Oh for Christ Sakes" added to the overall mood. I have to say that, while the compositions weren’t exactly what I hoped for, I sympathized with his frustration.

Technical difficulties continued this evening. During the performance of John Cage’s Solo for Voice 58 (18 Microtonal Ragas), the singer’s portable microphone stopped working and the monitors malfunctioned. Despite the problems, this was an incredible performance of a compelling piece. One of the most wonderful things about Cage’s music is its sense of humor, which was really what saved this performance. The singer was a bit too personally offended by the technical problems, but they were trying for the audience too. The highlight of the performance was the percussionists, Federico Sanesi and Ray Kaczynski. Both played perfectly yet with soul and sensitivity. It was difficult to tell which part of this piece was reductive: elements of Indian kathakali dance added rich visual interest, and the timbral interest and virtuosic percussion artists were aurally enthralling. (I suppose the advertising of the concert as "An Experiment in Indian Cuisine" was what attracted the dreadlocked, incense-burning, neo-spiritual crowd. I doubt the knew quite what to expect, but they seemed to enjoy what they heard.)

I cannot imagine the Exposition becoming a fixture on the new music scene at the present time. Yet, with a bit more attention paid to the technical aspects and a shot of publicity to attract larger audiences, the festival could be an impressive local event.

On another note, I am a great fan of John Cage’s philosophy and some of his music. In my favorite documentary about Cage, he observes the following (though I suspect he is paraphrasing some Zen philosophy of sorts): "I have nothing to say, and I am saying it." As far as I can tell, that pretty well describes this blog.

On another note, I am a great fan of John Cage’s philosophy and some of his music. In my favorite documentary about Cage, he observes the following (though I suspect he is paraphrasing some Zen philosophy of sorts): "I have nothing to say, and I am saying it." As far as I can tell, that pretty well describes this blog. Dobrou noc.

Tagged: Brno, concerts, music

Slow on the Uptake

A bill legalizing domestic partnerships was passed by the Chamber of Deputies of the Czech Parliament last week. The bill passed the Senate in January (Brno senator Jiří Zlatuška abstained). President Klaus, who officially opposes the bill and successfully vetoed an earlier attempt, claimed last December that the bill would "interfere too much in the lives of private residents." The current bill passed on 15 March with 101 votes for "ano" from the 177 members of Chamber who were present. The bill will take effect during June 2006.

A bill legalizing domestic partnerships was passed by the Chamber of Deputies of the Czech Parliament last week. The bill passed the Senate in January (Brno senator Jiří Zlatuška abstained). President Klaus, who officially opposes the bill and successfully vetoed an earlier attempt, claimed last December that the bill would "interfere too much in the lives of private residents." The current bill passed on 15 March with 101 votes for "ano" from the 177 members of Chamber who were present. The bill will take effect during June 2006.I claim little authority in talking about Czech politics so, to mix metaphors, I'm speaking on thin ice here. Yet the bill itself is mixed. While opening up some legal doors - it gives couples access to medical records and inheritance rights - it bars anyone involved in a partnership from adopting children. Thus it was a step toward legal equality but nothing even approaching a "separate but equal" status. (And shouldn't the end goal be a straightforward "equal" status anyway?) The bill was also passed in part through the strengthening (and more than a little worrisome) political alliance between the Social Democrat and Communist parties. (The Christian Democrats roundly opposed the issue.) Thus "tinged" (by association with the communist party), the issue may be more easily opposed in future discussions on the grounds of political ideology arising from social history rather than on the basis of social or moral concerns. For example Kateřina Dostálová, a long-time supporter and co-author of the bill, abstained from the vote, citing the way Premier Paroubek and the social democrats made this a "flagship" issue and rallying point. Thus the event could be seen as a vote to garner popular support for their leadership rather than a vote on a social issue. (My goodness, the political scene here can be worlds apart from the U.S. at times!) The bill also comes after a scare about the state of the "Czech family." Such "political" baggage may plague the issue in the future if the balance of power in the government shifts away from the conservative and communist parties.

Is the Czech Republic a bit slow on the uptake here? Granted, this bill makes the CR the only Central European country to support domestic partnerships. Over sixty percent of Czechs are thought to support same-sex marriages. Yet given Czech society's supposed openness and the country's political reputation as a haven for human rights (yes, this is the sort of sentiment you encounter in the guidebooks for tourists, but nonetheless it holds a place in the post-Communist national imaginary even among some Czechs though not all), I am surprised the bill took so long to get this far. But then, you have to start somewhere, and despite its shortcomings this bill seems a step in the right direction.

Information and sources:

Insight Central Europe report (in English)

Czech Radio story (in Czech) (and in English)

Registrované partnerství updates from STUD Brno (in Czech)

Tagged: Czech, politics, society, sociology, lgbt

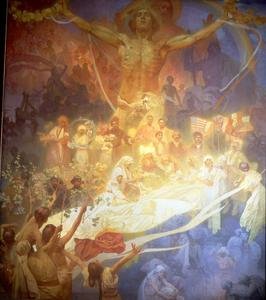

Slavic Epic Stolen

22 March 2006 [To be filed from South Moravia, someday in 2010] -- The residents of the South-Moravian town Moravský Krumlov woke up to find Alfons Mucha's Slavic Epic gone this morning. The Epic is a series of twenty canvases that each exceed four meters per side and was last worked on in 1928 though never completely finished. It depictes scenes from Slavic mythology and great moments in Slavic cultural history. The paintings were one of the few tourist draws for the small town. Mucha (1860-1939) was born in a neighboring village, but Krumlov has been the home of the epic throughout local memory. It is suspected that a ring of Prague bigwigs and power-brokers airlifted the canvases from the town's unguarded chateau sometime in the morning's wee hours. No sounds were heard, however, and authorities are puzzled as to how the twenty gargantuan canvases could have been smuggled away unbeknownst to local residents.

[To be filed from South Moravia, someday in 2010] -- The residents of the South-Moravian town Moravský Krumlov woke up to find Alfons Mucha's Slavic Epic gone this morning. The Epic is a series of twenty canvases that each exceed four meters per side and was last worked on in 1928 though never completely finished. It depictes scenes from Slavic mythology and great moments in Slavic cultural history. The paintings were one of the few tourist draws for the small town. Mucha (1860-1939) was born in a neighboring village, but Krumlov has been the home of the epic throughout local memory. It is suspected that a ring of Prague bigwigs and power-brokers airlifted the canvases from the town's unguarded chateau sometime in the morning's wee hours. No sounds were heard, however, and authorities are puzzled as to how the twenty gargantuan canvases could have been smuggled away unbeknownst to local residents. In one of the most bizarre aspects of this scandal, one small picture (seen at right), barely noticeable on the gallery's mammoth walls, was substituted. Art experts believe it to be a piece pilfered from the Hotel Hubertus in Valtice, last seen sometime in October 2005. The significance of the piece - somewhat collage-like in nature though reminiscent of an oil painting, it consists of a boat, sunlight, a palm tree, and a cottage - is unknown.

If the suspicions of Krumlov's mayor are correct, then this may be the latest coup by the Prague-based EnD Group (Engulf and Devour), which for some time has been attempting to move the paintings to Prague permanently. Krumlov police attempted to obtain a search warrant for a large, matchbox-like warehouse in the Stromovka Park, but were unsuccessful after an injunction from the Supreme Court of the Czech Republic blocked their efforts. A Mr. Kecal, spokesperson for the EnD group, denies any involvement.

Geraldine Mucha, the painter's daughter-in-law and a trustee of the Mucha Foundation, remarked: "There are two Krumlovs in this country: one is Český Krumlov and that is a little gem. And, it has had millions of foreign money poured into it and it is a gem. Now, this is Moravský Krumlov. Well, it's a nice village, but that's all it has: the Slav Epic." Now it has nothing. Off the record she indicated that she was inclined to believe the conspiracy theory but also offered the thought that perhaps a Japanese investor had organized the caper, spurred on by a girlfriend who was among the droves of Japanese art history students, all Mucha specialists, who toured Moravský Krumlov every summer. Ms. Mucha also suggested that the Prague group "want[s] to use those canvases as a lure for foreign tourists into a rather dead end of Prague [Stromovka Park]."

More details are reported by Czech Radio.

Tagged: Moravia, Mucha, Czech.

The Existence of Man as an Inner Task

21 March 2006

I couldn't pass up this photo. Yet another exciting event in Brno: a lecture on personal development, sponsored by the Rosicrucians. You may remember a previous photo that I blogged from merkwurdigliebe. He has a great selection of Brno photos at his flickr site that go a long way to capturing the feel of various parts of the city. Though to my knowledge there are not many Brno bloggers, quite a few photographers find the city of interest. Have a look at their work in the Brno pool at flickr.

Tagged: Brno, photography, Czech.

Tagged: Brno, photography, Czech.

Tuesday Dewdrops

Sitting at the kitchen table from IKEA, a Tchibo gift-mug at my right. I'm typing and drinking coffee - it's Turkish (that is, the grounds are just thrown in since I'm being Czech and have not sprung to buy any coffee-making paraphenalia), which means you have to drink it slowly and meditatively. Thoughtful or pensive?

It's now official spring, and not just by the calendar. There are nascent leaves in the buds on the tree outside my windows. This leaf was in the flowerbeds outside Burton Tower at University of Michigan. The photo was taken about six months ago, just a few days before I left Ann Arbor last fall.

It's now official spring, and not just by the calendar. There are nascent leaves in the buds on the tree outside my windows. This leaf was in the flowerbeds outside Burton Tower at University of Michigan. The photo was taken about six months ago, just a few days before I left Ann Arbor last fall.

A Spring Concert

The well-known cimbál band Hradišťan performed last Tuesday (14 March) in my neighborhood. Since it was close, I arrived late. The Musilka hall at "Omega" cultural center is not far from my new apartment, which gave me the idea that I would not have to hurry. This resulted in leaving the house at 19.30 and not arriving until after the concert began. I should have hurried. I did, however, catch most of the music. Hradišťan’s core instrumentation is relatively normal, that of a run-of-the-mill cimbalom band: primáš (first violin, Jiří Pavlica) and second violin (Michal Krystýnek), kontráš (viola, two players rotate in this position), kontrabas (bass, Dalibor Lesa), cimbál (Milan Malina), a reed and flute player (clarinet and whistles, David Burda), and a female singer (Alice Holubová). All the members double on vocals, and most of them sang as the lead at least once (except perhaps the bassist and violist).

The well-known cimbál band Hradišťan performed last Tuesday (14 March) in my neighborhood. Since it was close, I arrived late. The Musilka hall at "Omega" cultural center is not far from my new apartment, which gave me the idea that I would not have to hurry. This resulted in leaving the house at 19.30 and not arriving until after the concert began. I should have hurried. I did, however, catch most of the music. Hradišťan’s core instrumentation is relatively normal, that of a run-of-the-mill cimbalom band: primáš (first violin, Jiří Pavlica) and second violin (Michal Krystýnek), kontráš (viola, two players rotate in this position), kontrabas (bass, Dalibor Lesa), cimbál (Milan Malina), a reed and flute player (clarinet and whistles, David Burda), and a female singer (Alice Holubová). All the members double on vocals, and most of them sang as the lead at least once (except perhaps the bassist and violist).  The building was not another one of those communist cultural centers, which surprised me since its designation as a kulturní středisko (cultural center) has a socialist ring to it! Communist "cultural houses" pollute so many Czech towns and most were built in an architerually unfortunate 1960s style. The Omega's architecture--spare functionalist with perhaps some slight art deco influence--suggested that it was built in the 1920s or 30s. The hall was boxy, but did seem to have better sound than others I’ve been in, which I attributed arbitrarily to the earlier architectural style (at least there was no music from a nonstop Herna bar booming up through the floor as there was at a Jožka Černý concert back in December). The most obviously outdated elements were the ticket stubs: they were so old that the price was listed in "Kčs"--Czechoslovak crowns, which haven’t existed since 1993. I suspect that, in 1993, 190 crowns would have been an expensive concert; it seems a good price to me (nowadays that’s under $8).

The building was not another one of those communist cultural centers, which surprised me since its designation as a kulturní středisko (cultural center) has a socialist ring to it! Communist "cultural houses" pollute so many Czech towns and most were built in an architerually unfortunate 1960s style. The Omega's architecture--spare functionalist with perhaps some slight art deco influence--suggested that it was built in the 1920s or 30s. The hall was boxy, but did seem to have better sound than others I’ve been in, which I attributed arbitrarily to the earlier architectural style (at least there was no music from a nonstop Herna bar booming up through the floor as there was at a Jožka Černý concert back in December). The most obviously outdated elements were the ticket stubs: they were so old that the price was listed in "Kčs"--Czechoslovak crowns, which haven’t existed since 1993. I suspect that, in 1993, 190 crowns would have been an expensive concert; it seems a good price to me (nowadays that’s under $8).I squeezed past the people sitting next to the door to find an empty seat in the last row. As I was sitting down Pavlica was just finishing a few remarks and I heard him wish everyone a "friendly evening." The concert, he remarked, was to celebrate spring. This ended up slightly ironically since a few inches of snow had fallen over the weekend and there were still flakes in the air that evening. This was taken in good spirits, however, and the band played many songs from their album O slunovratu (Of the solstice) to show that we had not yet given up on summer’s return even if it was going slowly.

Hradišťan is certainly one of the most interesting and long-standing groups on the Moravian music scene. Since their founding as a folklore troup in the group has seen many changes. Most significant was probably the entrance of violinist Jiří Pavlica in 1975; he became the artistic director in 1978 and continues to guide the group. In addition to playing first violin he has involved the group in an extensive series of collaborations with Czech musicians and others from around the world, many of which were broadcast on Czech Television as the series Sešli se (“They came together”). He has also composed much of the groups recent repertory. Some of my favorites were "Modlitba za vodu" ("Prayer for Water,” on a text by Jan Skácel) and "Rozhovor a láska" ("Conversation and Love," also on a Skácel text but featuring a very summery instrumental interlude reminiscent of the Shire music from the recent Lord of the Rings score).

Modlitba za vodu by Jan Skácel

Modlitba za vodu by Jan SkácelUbývá míst kam chodívala pro vodu

má starodávná milá

kde laně tišily žízeň kde žila rosnička

a poutníci skláněli se nad hladinou

aby se napili z dlaní

Voda si na to vzpomíná

voda je krásná,voda má

voda má rozpuštěné vlasy

chraňte tu vodu

nedejte aby osleplo prastaré zrcadlo hvězd

Playing-wise the group seems almost too polished. This is not bad, but they often sound like a band playing in the studio rather than interacting with an audience. Some of this might be due to the sound engineer—everything was very dry and crisp through the speakers and the hall did not become boomy. The cimbál was miked particularly nicely, and the vocals were much clearer than is sometimes the case for similar groups. However, there is more to this polished sound than sound engineering: Hradišťan is very well-rehearsed and there is a tight sense of ensemble. Every beginning and ending was together, especially in tricky arrangements and songs with long or comlex verses. Such a crisp sense of ensemble only comes from extensive rehearsal and highly-trained musicians. (Pavlica, at least, studied violin performance at the Brno Conservatory and later composition at the Janáček Academy in Brno; earlier he also studied "cultural theory" at Palacký University in Olomouc.) It sounds like a larger ensemble than it is because of the blend. Also the singers and violinists can deftly change timbre to sound more ‘folky’ or more orchestral.

The hall was almost full, and it was obvious that Hradišťan is popular with the audience in Brno; I suspect most of their concerts are full. Why do people go to the concerts? Is it an identity thing? Is there a felt connection between Hradišťan’s "new" elements and older "Czech" folk music? They do not seem to advertise as a "folklore" group, yet it is that strand of their style which legitimizes their "Czech" status as. "Folklore" seems to be a category that is conceived most of the time as static, yet Hradišťan’s music is vibrant and combines many non-folkloric elements. In fact, as commentator Ondřej Bezr noted after an interview with Pavlica, "it is fascinating to realize that Hradišťan – similar to some Czech folk musicians of the last twenty years – has convinced the ‘alternative’ public and even young listeners, that ‘folklore’ is not a swear word" (in Pětadvacet [Rozhovory s českými muzikanty] [Brno: Petrov, 2004], p. 37). Yet with all the "new" elements they incorporate--many of the songs are their own and utilize Czech folk instruments primarily for unique sounds--I can’t help but asking if they are really departing from Czech folklore or merely from a stream of music that draws Czech instruments and features songs with Czech-language texts? They are often dubbed "crossover" (in English, crossover) artists here, but would they be perceived that way outside the country? What are they crossing over? How is that concept understood here? Do musicians themselves use it to describe their music or does it have a disparaging ring? In the end, it is Pavlica’s personality and compelling musicianship that has kept the group popular with audiences and musically vibrant. A listener might well be impressed first by the quality of their musicianship than their obviously deep knowledge of Czech folk music. This is, perhaps, why they have become and continue to be so popular.

(My photos did not turn out so I have chosen a few from their website. 1) Hradišťan in Mongolia during a 2002 tour; 2) The venue, cultural center "Omega" on Musilka street; 3) Modlitba za vodu by Václav Mach-Koláčný.)

Tagged: music, concerts, Brno, Czech.

The Quietest Tram in the East

18 March 2006

[I have a habit of going to the grocery store late. It’s less crowded, I’ve got the energy for it, and it usually seems like a good idea, until your trip turns into something else completely.]

Interspar was closing and the parking lot was bare. All the other customers had left. Though hardly any light got in through the grimy windows, I could tell it was a scorcher outside. Waves of heat rose from the pavement, where the hard-packed mud cracked and crinkled like badly chapped lips. I stepped out of the swinging wooden doors and glanced to my left. The coast was clear. I swaggered to the right—toward the homeward stage-tram line—my footsteps echoed on the hollow wooden sidewalks. A tumbleweed blew across the tarmac as I reached the midway point. It was a familiar stretch, but things seemed quieter than usual. I wanted to open my water bottle and stop for a drink. (It was full of slivovice. Domácí. Water’s for softies, and we’re a tough bunch out here on the frontier.) No time to look around: I could see the cloud of dust the tram was kicking up in the distance. It rose like the plume of a distant cooling tower and obscured the silhouette of the ruined mining towers on distant Špilberk plateau. A yellow pall—soot from the Zetor refinery across the dry riverbed—hung in the air

Interspar was closing and the parking lot was bare. All the other customers had left. Though hardly any light got in through the grimy windows, I could tell it was a scorcher outside. Waves of heat rose from the pavement, where the hard-packed mud cracked and crinkled like badly chapped lips. I stepped out of the swinging wooden doors and glanced to my left. The coast was clear. I swaggered to the right—toward the homeward stage-tram line—my footsteps echoed on the hollow wooden sidewalks. A tumbleweed blew across the tarmac as I reached the midway point. It was a familiar stretch, but things seemed quieter than usual. I wanted to open my water bottle and stop for a drink. (It was full of slivovice. Domácí. Water’s for softies, and we’re a tough bunch out here on the frontier.) No time to look around: I could see the cloud of dust the tram was kicking up in the distance. It rose like the plume of a distant cooling tower and obscured the silhouette of the ruined mining towers on distant Špilberk plateau. A yellow pall—soot from the Zetor refinery across the dry riverbed—hung in the air

By now the setting sun cast long ochre shadows. The dark splotch cast by the tram had already reached the boarding platform even though the carriage itself was still in the distance. Silence commenced when my footsteps ceased at the platform. A dog barked in the distance. Some dust blew up in the parking lot and swooshed like a crash of thunder. I waited, exposed to the whimsies of the landscape, alone. Even if someone else had been there, we wouldn’t have looked at each other. We got rid of conversation along with the last water wells. (Neither were necessary. We have plenty of slivovice.)

The tracks began their singing, quietly at first and then rising to siren-like wailing, as the tram approached. By the time it reached the platform the rumble had grown deafening. This wasn’t any old route, it was the Number 4 Special and it’s not for wimps this one. A few weeks back the Special was attacked as it came through the pass at Úvoz. That’s the narrow pass between the suburbs and the town proper. It’s wild over there, so they pick the drivers for this route carefully. You can’t be afraid of knocking an old woman out of her seat by speeding uphill around sharp corners when being pursued by a crowd of rabid students. Just push the throttle to the dashboard and get the heck out of Škoda (as we say).

The doors creaked open. Silence returned. I peered inside the carriage. It was too dark to see much, but it was even quieter than usual. So quiet that you could have heard somebody’s cell phone ringing, probably with one of those stupid pop songs. They should outlaw softy ring tones like that; I’ve got mine set to the “Slivovice Barrel Polka.” I got in. Even if the tram had been hijacked and was full of bandits, I could fend off the riff-raff if necessary (we finally got plastic bottles so none of my purchases would be in danger of breaking). My eyes adjusted as I stood in doorway, and I saw my silhouette in the doorway reflected in a pack of dusty eyes. At first the eyes belonged to a large black lumps, but as my pupils contracted I saw that it was just a bunch of natives. Harmless.

Silence. There were a few open seats in the back. Was it worth the risk to walk past the crowd in the front and to sit down? No one stood in my way, but challenges can lurk in silence like this, or under the seats and in other dark spaces. I looked around, they looked back at me. Silence. I took a step. No response. The gravel on the floor scraped as I turned my heel. Then there was silence again. Gaining confidence, I took another step. Then another. I heard the voice of one advisor in the back of my head, “Forge ahead.” I decided to go for it and bounded for safety at the back of the tram. In one arcing leap I sailed over their heads, causing more of a disturbance on the Special than has been heard for some time, and reached sanctuary at the back. I adjusted my backpack straps and assessed the situation. At least for the moment, it seemed that I had secured my ride home. I wiped the sweat from my brow, took that long-awaited swig of slivovice, and smiled.

(Photo from that quintessential goulash western and musical, Lemonade Joe, or, The Horse Opera.)

Tagged: Czech, Brno, westerns

Interspar was closing and the parking lot was bare. All the other customers had left. Though hardly any light got in through the grimy windows, I could tell it was a scorcher outside. Waves of heat rose from the pavement, where the hard-packed mud cracked and crinkled like badly chapped lips. I stepped out of the swinging wooden doors and glanced to my left. The coast was clear. I swaggered to the right—toward the homeward stage-tram line—my footsteps echoed on the hollow wooden sidewalks. A tumbleweed blew across the tarmac as I reached the midway point. It was a familiar stretch, but things seemed quieter than usual. I wanted to open my water bottle and stop for a drink. (It was full of slivovice. Domácí. Water’s for softies, and we’re a tough bunch out here on the frontier.) No time to look around: I could see the cloud of dust the tram was kicking up in the distance. It rose like the plume of a distant cooling tower and obscured the silhouette of the ruined mining towers on distant Špilberk plateau. A yellow pall—soot from the Zetor refinery across the dry riverbed—hung in the air

Interspar was closing and the parking lot was bare. All the other customers had left. Though hardly any light got in through the grimy windows, I could tell it was a scorcher outside. Waves of heat rose from the pavement, where the hard-packed mud cracked and crinkled like badly chapped lips. I stepped out of the swinging wooden doors and glanced to my left. The coast was clear. I swaggered to the right—toward the homeward stage-tram line—my footsteps echoed on the hollow wooden sidewalks. A tumbleweed blew across the tarmac as I reached the midway point. It was a familiar stretch, but things seemed quieter than usual. I wanted to open my water bottle and stop for a drink. (It was full of slivovice. Domácí. Water’s for softies, and we’re a tough bunch out here on the frontier.) No time to look around: I could see the cloud of dust the tram was kicking up in the distance. It rose like the plume of a distant cooling tower and obscured the silhouette of the ruined mining towers on distant Špilberk plateau. A yellow pall—soot from the Zetor refinery across the dry riverbed—hung in the air By now the setting sun cast long ochre shadows. The dark splotch cast by the tram had already reached the boarding platform even though the carriage itself was still in the distance. Silence commenced when my footsteps ceased at the platform. A dog barked in the distance. Some dust blew up in the parking lot and swooshed like a crash of thunder. I waited, exposed to the whimsies of the landscape, alone. Even if someone else had been there, we wouldn’t have looked at each other. We got rid of conversation along with the last water wells. (Neither were necessary. We have plenty of slivovice.)

The tracks began their singing, quietly at first and then rising to siren-like wailing, as the tram approached. By the time it reached the platform the rumble had grown deafening. This wasn’t any old route, it was the Number 4 Special and it’s not for wimps this one. A few weeks back the Special was attacked as it came through the pass at Úvoz. That’s the narrow pass between the suburbs and the town proper. It’s wild over there, so they pick the drivers for this route carefully. You can’t be afraid of knocking an old woman out of her seat by speeding uphill around sharp corners when being pursued by a crowd of rabid students. Just push the throttle to the dashboard and get the heck out of Škoda (as we say).

The doors creaked open. Silence returned. I peered inside the carriage. It was too dark to see much, but it was even quieter than usual. So quiet that you could have heard somebody’s cell phone ringing, probably with one of those stupid pop songs. They should outlaw softy ring tones like that; I’ve got mine set to the “Slivovice Barrel Polka.” I got in. Even if the tram had been hijacked and was full of bandits, I could fend off the riff-raff if necessary (we finally got plastic bottles so none of my purchases would be in danger of breaking). My eyes adjusted as I stood in doorway, and I saw my silhouette in the doorway reflected in a pack of dusty eyes. At first the eyes belonged to a large black lumps, but as my pupils contracted I saw that it was just a bunch of natives. Harmless.

Silence. There were a few open seats in the back. Was it worth the risk to walk past the crowd in the front and to sit down? No one stood in my way, but challenges can lurk in silence like this, or under the seats and in other dark spaces. I looked around, they looked back at me. Silence. I took a step. No response. The gravel on the floor scraped as I turned my heel. Then there was silence again. Gaining confidence, I took another step. Then another. I heard the voice of one advisor in the back of my head, “Forge ahead.” I decided to go for it and bounded for safety at the back of the tram. In one arcing leap I sailed over their heads, causing more of a disturbance on the Special than has been heard for some time, and reached sanctuary at the back. I adjusted my backpack straps and assessed the situation. At least for the moment, it seemed that I had secured my ride home. I wiped the sweat from my brow, took that long-awaited swig of slivovice, and smiled.

(Photo from that quintessential goulash western and musical, Lemonade Joe, or, The Horse Opera.)

Tagged: Czech, Brno, westerns

Petite Bourgeois

17 March 2006 Yesterday afternoon I was standing in my bathroom doing laundry. Unlike many European apartments, mine has a true "bath"room. Usually you find the toilet in a room of its own and the sink and bath in a room of their own. I have one room for everything (including the hot water heater), except a washing machine. So there I was washing a few things in the sink.

Yesterday afternoon I was standing in my bathroom doing laundry. Unlike many European apartments, mine has a true "bath"room. Usually you find the toilet in a room of its own and the sink and bath in a room of their own. I have one room for everything (including the hot water heater), except a washing machine. So there I was washing a few things in the sink. There has been mention of laundry on this blog before: some Americans seem to have issues with the size of European washers. Well, I didn't have a washing machine in my old apartment, either. This would not be such an issue if there were pay laundromats around, but they only exist in Prague. I've survived. It's now obvious that one can exist without washing machines entirely, whether free or pay, small or large. (Who says size doesn't matter?) You can be your own washing machine!

Here's the proof:

That's what I was doing until I realized that hand washing is hard work. (What a lazy bum!) I could afford to use a laundry service, and I had an old advertisement from "AGIplus" washers and cleaners. Simple, I thought, I can just take this shirt, this pair of pants, and these sheets, and then I won't have to worry about it anymore. The advertisement gave the address Botanická 61. According to my map, the bus that goes by my apartment also stops at that street. Simple.

Or so it seemed. The bus was not too crowded. A good sign. I easily found Botanická street. Then go to number 61, I thought, and I'm set.

Problem 1: The bus only stops next to number 26.

Not to worry, I thought, just keep walking in the direction of increasing numbers.

Problem 2: That's not really how street numbers work here.

Sometimes they run in seuence, sometimes they kind of sort of do. The latter type are often deceivingly similar to the sequential ones, but there will suddenly be a chunk missing ("Wow, how did they ever fit 25-63 1/2 in that tiny alleyway!") or they will start from both ends of the street ("Hey, why are the numbers on that side going up while the ones on this side are going down?"). This is further complicated by the "house numbers." Apparently since the Austro-Hungarian times, every house was numbered for the convenience of the landowners--it was a way for rulers to limit the movement of people (you had to have permission to move) and allowed the landowners to ensure that everyone was paying their rent and doing their work. At some other time, I presume, "street numbers" were added. Ostensibly for the convenience of locating a place. Now the systems coexist and, in certain cases, this is confusing since many houses have signs for both numbers. To Czechs used to carrying around this useless bureaucratic information with them at all times - as everyone does, but of different sorts - it is not confusing at all. Back on Botanická street, I was feeling lost.

Problem 3: No number 61 in sight.

There was number 56, then a street, an empty lot, and number 66. The empty lot appeared to be a corner park. There was no evidence that a laundry had recently burned down or removed by alien spacecraft. I scoured the alleyways and courtyards behind these houses. Best to make sure. Still no sign. The advertisement was just a photocopy, so perhaps this was just some elaborate hoax.

I kept walking. And walking. Just A few blocks farther. Finally, there it was--number 61, nestled on the last block of the street, completely out of sequence. (The street actually continued under another name, but that would only cause more confusion. I suppose the numbers on Botanická had become so confused they finally just gave up and renamed the rest of the street.)

Problem 4: No "AGIplus" cleaners.

But, adding to my surprise at actually finding number 61, there was another laundry service, which gave no indication of being "AGI." Since I had come all this way, I didn't really care what the name was and went in anyhow.

Sometimes you have to take what you can get. (I'll see if I feel that way when the laundry comes back, assuming the place hasn't closed down by then.)

Tagged: laundry, Brno, Czech

For Today

Today's deep thoughts from a new toy I was exploring. A friend got me into Donnie Darko last year. This dialogue from the extended version is a conversation between Donnie and his English teacher Mrs. Pommeroy. Mrs. Pommeroy is later fired, though I think she resigns first. As I recall the American flag is prominent in the classroom. The scene is not critical of primary/secondary education systems and, I suppose, to increase the believability of a high school student-teacher relationship, was cut. The dialogue did add to the movie, however, since it builds Donnie's outsider status and plants the seeds for the destruction of the school (and other things). And, of course, who are the rabbits?

Tagged: Donnie Darko, wikiquote, film

[Discussing Watership Down]

Karen Pommeroy: This could be the death of an entire way of life, the end of an era...

Donnie: Why should we care?

Karen Pommeroy: Because the rabbits are us, Donnie.

Donnie: Why should I mourn for a rabbit like he was human?

Karen Pommeroy: Are you saying that the death of one species is less tragic than another?

Donnie: Of course. The rabbit's not like us. It has no... keen look at something in the mirror, it has no history books, no photographs, no knowledge of sorrow or regret... I mean, I'm sorry, Miss Pommeroy, don't get me wrong; y'know, I like rabbits and all. They're cute and they're horny. And if you're cute and you're horny, then you're probably happy, in that you don't know who you are and why you're even alive. And you just wanna' have sex, as many times as possible, before you die... I mean, I just don't see the point in crying over a dead rabbit! Y'know, who... who never even feared death to begin with.

Tagged: Donnie Darko, wikiquote, film

That'll Teach Ya

16 March 2006

I didn't check email for a week. So much of import has happened while I was gone. It was astonishing! And it only took one, two, three-plus hours.

Just a smattering of things that I missed:

I almost get the feeling that, had I been there to respond, I might have been able to help with something. Reorganize a meeting, perhaps? Help someone find an optometrist in a city where I do not live? Help cure AIDS? So many missed opportunities to be a good samaritan. Alas. That's the joy of checking email every&*)^#%&day.

In honor of being an email curmudgeon, I started a blog email address. You know, to increase credibility. You can find it by clicking on "email me" in the right-hand sidebar. Perhaps I can get out a few phishing scams, offer personal services, sell cheap Canadian medications, or other tempting offers for your inboxes. Until, that is, my new address is discovered.

Tagged: email, spam

Just a smattering of things that I missed:

- performances of the "first New World Opera" in Ann Arbor, Michigan

- symposium in connection with above event

- job offers in Tashkent, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan [insert your favorite Central-Asian city here]

- plans to organize a lunch with a senior musicologist (only six time zones away)

- a faculty meeting that graduate students couldn't go to anyway

- organizing a meeting of a transportation committee in Ann Arbor

- a series of job talks by anthropologists in, you guessed, Ann Arbor

- CfPs for a number of international conferences and the Society for Ethnomusicology reminders

- an art opening in Brno

- sales at amazon

- "coffee" with my congressional representative in upper Michigan

- a missed dinner date at Masaryk in Brno

- a curious "Graduate Student Dance Party" in A2, allegedly free

- chances to save my account at Comerica bank, where I never had an account

- unsolicited answers to personal ads that were never placed

- a movie that showed five days ago

- "Graduate student government" re-election campaigns

- information about joining the Peace Corps

- a changed meeting plan for, well, you get the idea...

I almost get the feeling that, had I been there to respond, I might have been able to help with something. Reorganize a meeting, perhaps? Help someone find an optometrist in a city where I do not live? Help cure AIDS? So many missed opportunities to be a good samaritan. Alas. That's the joy of checking email every&*)^#%&day.

In honor of being an email curmudgeon, I started a blog email address. You know, to increase credibility. You can find it by clicking on "email me" in the right-hand sidebar. Perhaps I can get out a few phishing scams, offer personal services, sell cheap Canadian medications, or other tempting offers for your inboxes. Until, that is, my new address is discovered.

Tagged: email, spam

Who are the Europeans?

The University of Michigan at Ann Arbor

Center for European Studies and European Union Center

present

CONVERSATIONS ON EUROPE LECTURE SERIES

An interesting lecture announcement. But what about cultural policies and artists? Do they not also shape the European cultural identity and landscape, particularly in local communities?

Center for European Studies and European Union Center

present

CONVERSATIONS ON EUROPE LECTURE SERIES

"The Dilemma of European Integration: Who are the Europeans (and why does that matter for politics)?"

A lecture by Neil Fligstein, Professor of Sociology, U-C Berkeley

Thursday, March 30, 4:20 pm

Room 1636, International Institute

The main mechanism of further political integration is not to be located in Brussels, but instead within the populations of Western Europe who have increasingly gained as a result of the EU tearing down trade barriers. Managers, professionals, educated people, people with higher incomes, and the young have increasingly found themselves in situations where they routinely interact with their counterparts from other countries. These are the people who have come to see themselves as Europeans and who have pushed forward the integration project. Yet, the future of the European project now turns on the degree to which other parts of the population become enmeshed in more routine social relations with their counterparts in other countries.

An interesting lecture announcement. But what about cultural policies and artists? Do they not also shape the European cultural identity and landscape, particularly in local communities?

Pozor!

For those of you able to attend, the following concert will feature two movements from Hubert's chamber orchestra piece.

Informace:

Komorní koncert katedry skladby

27.3., po., 19.30

Sál Martinů, Hudební fakulta Akademie múzických umění (HAMU), Malostranské Náměstí 13

Kč 90,- (číslovaná verze sálu)

účinkují Komorní orchestr Berg, dirigent Peter Vrábel

Zahrají skladby z děl posluchačů katedry

Information:

Chamber Concert of the Composition Department, Academy of Musical Arts (HAMU)

Monday, 27 March, 7:30 p.m.

Martinů Hall, HAMU, Malostranské Náměstí 13, Prague

Admission: 90 crowns

performers: Berg Chamber Orchestra, conducted by Peter Vrábel

program: works by students in the department

A Little LingAnthro for You

It can be disorienting sometimes to do fieldwork. Not the least of one's worries is, what the heck is fieldwork anyway now that it's been "problematized" (along with just about any humanities discipline I can think of). It can also be a chore to live in a new place and to try speaking a new language. So I was glad to find solace in a (relatively) recent ethnography, Keith Basso's Wisdom Sits in Places: Landscape and Language among the Western Apache (Albuquerque: U. of New Mexico Press, 1996). One comfort of this book is that it makes no self-doubting apologies about representation and power, issues that have been undermining ethnography for the last few decades.

When I got here back in September I was thinking I knew some aspects of Czech culture pretty well. But that was quickly out the window. It can be deceptively "familiar" here at times because it is a European culture. There are a lot of things I'm used to. (Does this partly explain the dearth of ethnography in Europe? Too many people that do the stuff think it's just not interesting enough?) Well, just when you think you are finally getting close to "finding your feet" in a culture, as Clifford Geertz put it, one finds that the ground is still far away. It makes me think of the people in The Phantom Toll Booth who grow from the head downwards. Instead of getting taller and taller, they float above the ground as children and their legs don't reach all the way to the ground until they "grow up." As far as I'm concerned, I guess there is still some growing to do.

An unfamiliar landscape, like an unfamiliar language, is always a little daunting, and when the two are encountered together--as they are, commonly enough, in those out-of-the-way communities where ethnographers tend to crop up--the combination may be downright unsettling. From the outset, of course, neither landscape nor language can be ignored. On the contrary, the shapes and colors and contours of the land, together with the shifting sounds and cadences of native discourse, thrust themselves upon the newcomer with a force so vivid and direct as to be virtually inescapable. Yet for all their sensory immediacy (and there are occasions, as any ethnographer will attest, when the sheer constancy of it grows to formidable proportions) landscape and discourse seem resolutely out of reach. Although close at hand and tangible in the extreme, each in its own way appears remote and inaccessible, anonymous and indistinct, and somehow, implausibly, a shade less than fully believable. And neither landscape nor discourse, as if determined to accentuate these conflicting impressions, may seem the least bit interested in having them resolved. Emphatically "there" but conspicuously lacking in accustomed forms of order and arrangement, landscape and discourse confound the stranger's efforts to invest them with significance, and this uncommon predicament, which produces nothing if not uncertainty, can be keenly disconcerting.

When I got here back in September I was thinking I knew some aspects of Czech culture pretty well. But that was quickly out the window. It can be deceptively "familiar" here at times because it is a European culture. There are a lot of things I'm used to. (Does this partly explain the dearth of ethnography in Europe? Too many people that do the stuff think it's just not interesting enough?) Well, just when you think you are finally getting close to "finding your feet" in a culture, as Clifford Geertz put it, one finds that the ground is still far away. It makes me think of the people in The Phantom Toll Booth who grow from the head downwards. Instead of getting taller and taller, they float above the ground as children and their legs don't reach all the way to the ground until they "grow up." As far as I'm concerned, I guess there is still some growing to do.

*

15 March 2006

*Please note, sarcasm has not been completely deleted from this blog, but it does not necessarily reflect the position and opinions of the Editor.

Paneláky

Panel houses in Bystrc, a northwestern Brno suburb. The light was perfect when I visited there in January and almost made them look attractive. Some Czechs call them "rabbit hutches." I imagine they would be quite luxurious if you were a rabbit, though I'm not sure.

If you want to see more of my pictures, I have a photo page at flickr. Just click here to see pictures that don't make it onto the blog.

I've also syndicated the blog's feed on feedburner (info), so go ahead and subscribe to the blog. You won't have to come here every time you want an update! Click here or on the feed icon at the bottom of the right-hand sidebar. Hey, it's something to do.

If you want to see more of my pictures, I have a photo page at flickr. Just click here to see pictures that don't make it onto the blog.

I've also syndicated the blog's feed on feedburner (info), so go ahead and subscribe to the blog. You won't have to come here every time you want an update! Click here or on the feed icon at the bottom of the right-hand sidebar. Hey, it's something to do.

Back in the ol' ČSR

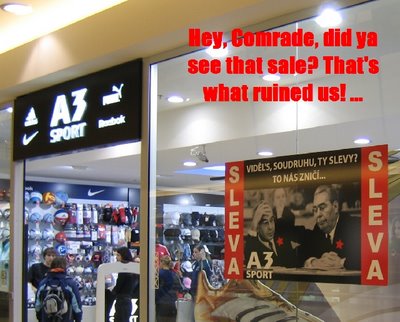

Upon returning to Brno from North Moravia. Taken in Galerie Vaňkovka, the mall across from the central bus station.

Good ol'

Good ol' evil capitalist mega-corporate conglomerate Adidas. Gets 'em every time.

Tagged: advertising, Communism.

Good ol'

Good ol' Tagged: advertising, Communism.

Berlin

14 March 2006 Last week I attended a conference in Berlin. Basically it was a venue to brag about how much money they pump into student exchange programs and to show off. The entire week was about "networking" and, note the lack of sarcasm here, a shortage of any substantive panel discussions plus a bunch of tours that were limited to twenty (20) participants each. Since the convenors were German they actually stuck to this attendance policy (although I did not hear that anyone was reprimanded for not showing up). I suppose I am slightly disgruntled because I was not allowed to go on all the tours I wanted. Or perhaps because my bankcard was denied at all ATMs, which meant that I had to sponge off everyone else or starve slowly by eating the standard finger-food "dinner" provided at receptions. (The other option was to starve more quickly in the endless lines at the buffet tables.) Evening receptions were also wrapped up at exactly the time listed on the conference program, which of course nipped any networking a person had finally got the guts to engage in, in the bud.

Last week I attended a conference in Berlin. Basically it was a venue to brag about how much money they pump into student exchange programs and to show off. The entire week was about "networking" and, note the lack of sarcasm here, a shortage of any substantive panel discussions plus a bunch of tours that were limited to twenty (20) participants each. Since the convenors were German they actually stuck to this attendance policy (although I did not hear that anyone was reprimanded for not showing up). I suppose I am slightly disgruntled because I was not allowed to go on all the tours I wanted. Or perhaps because my bankcard was denied at all ATMs, which meant that I had to sponge off everyone else or starve slowly by eating the standard finger-food "dinner" provided at receptions. (The other option was to starve more quickly in the endless lines at the buffet tables.) Evening receptions were also wrapped up at exactly the time listed on the conference program, which of course nipped any networking a person had finally got the guts to engage in, in the bud.  I was not as enchanted as I was with Vienna. Berlin is more vibrant. It's also more expensive than Vienna. As you can see from the illustration, the removal of grey paint from East German buildings is almost completed... The city is also known for "progressive" social mores and wide cultural diversity, which was a welcome relief/variety for the Czech and Slovak delegates. I particularly enjoyed the trip to the Turkish market with Megan and the wonderful Indian food. (It was so good to have a bit of spice on the palette. Even my American colleague Tim and his girlfriend, who invited me over for dinner, cooked a just-spicy-enough dim aloo.)

I was not as enchanted as I was with Vienna. Berlin is more vibrant. It's also more expensive than Vienna. As you can see from the illustration, the removal of grey paint from East German buildings is almost completed... The city is also known for "progressive" social mores and wide cultural diversity, which was a welcome relief/variety for the Czech and Slovak delegates. I particularly enjoyed the trip to the Turkish market with Megan and the wonderful Indian food. (It was so good to have a bit of spice on the palette. Even my American colleague Tim and his girlfriend, who invited me over for dinner, cooked a just-spicy-enough dim aloo.)

There is also the question of transparency in society, which extends of course to national politics. There's never enough. What is really going on? What are those politicians doing and why? To compensate for the perceived lack of such transparency, the hotel featured glass bathrooms. (Sorry, did I just steal one of the "jokes" from the preliminary opening speeches? oops.) The bathrooms were of great interest since the majority of roommates were unacquainted at first, as is standard for students at any conference of this sort. As they say, a man who lives in a glass house is either German or an exhibitionist. This described only a few conference participants, so the hotel wasn't exactly "number one" in our book. It was still pretty nice, though.

We also saw the impressively unintelligible and uninspiring installation Hommage à Picasso by Hanne Darboven at the Deutsche Guggenheim. The installation was about time and originality. Rich possibilities. As the brochure has it, Darboven’s "realization that the digits designating dates on the Gregorian calendar could serve as a neutral, 'graphic equivalent for the basically nonvisual phenomenon of time' allowed her to engage in the satisfying act of writing without describing. . . . She also incorporated into many of her works the German word Heute, meaning 'today', which she crossed out to depict the transformation of the present into the past" (quoting Klaus Honnef). Deep thoughts. Fortunately, it was free on Mondays. Even so, Alex and I spent a few euros on discounted 2006 planners. Possibly the endless calendrical number sheets that comprise most of the exhibit addled our sense of time. The exhibition is open until April 2006.

Then there were the Academy Awards which, though not all of us found them on television (and those of us who did did not inform everyone), were unsatisfying to most viewers. Brokeback Mountain, an adaptation of Annie Proulx's short story, was profound and visceral. Should it have won more awards? I don't know, and I have not seen the competition. However, Proulx's caustic expose of the award ceremony captured some of my feelings about the whole event. Somehow, in fact, it vaguely reminds of a certain conference . . .

After a good deal of standing around admiring dresses and sucking up champagne, people obeyed the stentorian countdown commands to get in their seats as "the show" was about to begin. There were orders to clap and the audience obediently clapped. From the first there was an atmosphere of insufferable self-importance emanating from "the show" which, as the audience was reminded several times, was televised and being watched by billions of people all over the world. Those lucky watchers could get up any time they wished and do something worthwhile, like go to the bathroom. As in everything related to public extravaganzas, a certain soda pop figured prominently. There were montages, artfully meshed clips of films of yesteryear, live acts by Famous Talent, smart-ass jokes by Jon Stewart who was witty and quick, too witty, too quick, too eastern perhaps for the somewhat dim LA crowd. . . .

Everyone thanked their dear old mums, scout troop leaders, kids and consorts. More commercials, more quick wit, more clapping, beads of sweat, Stewart maybe wondering what evil star had lighted his way to this labour. Despite the technical expertise and flawlessly sleek set evocative of 1930s musicals, despite Dolly Parton whooping it up and Itzhak Perlman blending all the theme music into a single performance (he represented "culchah"), there was a kind of provincial flavour to the proceedings reminiscent of a small-town talent-show night. Clapping wildly for bad stuff enhances this. (In full)

Pardon the long quote, but I like Proulx's prose. I wonder where she learned to cut to the quick so quickly. Her commentary also led me to a review that captures some highlights of the film and story.

Of course, the trip had its high points. There was a fabulous concert, and the headliner was my Prague friend Hubert. (Well, he was actually the only living composer featured in the entire evening, so he didn't have much choice.) Then there was the public art of Berlin. Scantily clad for the most part, but they use that fabric in other, more surprising, ways...

And in fact the city did grow on me quite a lot. Here was something GKJ might have liked.

the blog

There may have been a few changes during the recent interruptions in blog life. The blog will still have the same general focus, but March has been dragging on and there hasn't been enough humor. I may sound a bit sarcastic at times. Perhaps it's the inner cultural critic. Perhaps it's "academics." Perhaps it's not enough structure. Perhaps the novelty has worn off. I have, however, taken my brother's advice at face value and do not intend to go emo on you. Says Wikipedia: "Dark colors and long hair are a very popular in emo culture." My color scheme is currently 'a very popular' yet light [one chosen from Blogger's templates], though I have made a pact not to get a haircut for a few weeks. Then there is the footwear, "Converse All-Star style shoes are common . . . as are Vans shoes." I'm currently a Baťa-shoe guy, which does not fit the model. Not to mention that I can't really believe in a 'subculture' that comes with a guide.

There may have been a few changes during the recent interruptions in blog life. The blog will still have the same general focus, but March has been dragging on and there hasn't been enough humor. I may sound a bit sarcastic at times. Perhaps it's the inner cultural critic. Perhaps it's "academics." Perhaps it's not enough structure. Perhaps the novelty has worn off. I have, however, taken my brother's advice at face value and do not intend to go emo on you. Says Wikipedia: "Dark colors and long hair are a very popular in emo culture." My color scheme is currently 'a very popular' yet light [one chosen from Blogger's templates], though I have made a pact not to get a haircut for a few weeks. Then there is the footwear, "Converse All-Star style shoes are common . . . as are Vans shoes." I'm currently a Baťa-shoe guy, which does not fit the model. Not to mention that I can't really believe in a 'subculture' that comes with a guide. But somewhere there still lurks the tongue-in-cheekness you've come to expect.

Experience: Seeing Or Believing?

What we call the landscape is generally considered to be something "out there." But, while some aspects of the landscaape are clearly external to both our bodies and our minds, what each of us actually experiences is selected, shaped, and colored by what we know.

--Barrie Greenbie, Spaces: Dimensions of the Human Landscape

--Barrie Greenbie, Spaces: Dimensions of the Human Landscape

Winter Getting to You?

Went to Berlin. Went skiing at Pustevny. Back in Brno.

I didn't get a chance to sign the petition to end winter. According to reports, a group of protestors gathered in front of Brno's New Town Hall on Monday between 16.15 and 16.30 to protest winter and deliver their petition to mayor Richard Svoboda. The mayor - in an "exagerrated" response - said, "I will support the end of winter at the next meeting of the town council."

I'm all for fun and games, but do city officials and citizens have nothing better to do? How about an ordinance that requires people to shovel snow from their sidewalks? Or one to require the spreading of salt in order to reduce ice buildup? The construction of sidewalk roofs so pedestrians are not in constant danger of falling snow and ice? Or entirely handicap accessible trams? Or bike lanes along city streets?

Not to mention that winter is a wonderful time of year and they should make the most of it. Try building up the romance of the city in winter to attract some tourists from Prague!

I didn't get a chance to sign the petition to end winter. According to reports, a group of protestors gathered in front of Brno's New Town Hall on Monday between 16.15 and 16.30 to protest winter and deliver their petition to mayor Richard Svoboda. The mayor - in an "exagerrated" response - said, "I will support the end of winter at the next meeting of the town council."

I'm all for fun and games, but do city officials and citizens have nothing better to do? How about an ordinance that requires people to shovel snow from their sidewalks? Or one to require the spreading of salt in order to reduce ice buildup? The construction of sidewalk roofs so pedestrians are not in constant danger of falling snow and ice? Or entirely handicap accessible trams? Or bike lanes along city streets?

Not to mention that winter is a wonderful time of year and they should make the most of it. Try building up the romance of the city in winter to attract some tourists from Prague!

Wie ist Wien?

04 March 2006

What is Vienna like, that is? It's great. My visit made me so happy. People there just seem to enjoy life. While I was surfing the web yesterday I came across a page that said the city is consistently rated as the number one place to live when compared with other European. It has such a rich cultural history, the Imperial palaces in the center, and, reportedly, has relatively cheap prices when compared with other European capitals. (I don't know whether this last is true as it seems expensive compared to Brno. But then, that's a matter of perspective.)

There are a lot of ways that you can tell you've left the Czech Republic. You know you’re not in Brno anymore when

It's the little things that just make a person feel happy. One of my favorites is the sound of the the ticket stampers. In Czech metro systems (Prague, Brno, Olomouc, etc.) the ticket stamping machine goes "bzzzzzz" when you validate your ticket. It's kind of like, "Hey! Go away! I stamped your ticket already! NEXT!" In Vienna they go "ding." You think, "Ah, my ticket has been validated. Thank you." The ticket stamper indicates, "Have a nice day. Next, if you please." It's such a luxury when we find life in the details.

There are a lot of ways that you can tell you've left the Czech Republic. You know you’re not in Brno anymore when

-you don’t have to pay to use the toilet

-you do have to pay to use the coat-desk at the concert hall

-you can use credit card to buy your metro tickets

-only fancy cheeses are fried, and they come with cranberries on the side

-beer costs more than mineral water

-some trams are completely barrier-free

-all of the information booth employees speak English and are happy to tell all about the city (they even give free maps!!)

-people might actually look around while on the street

-people make way for each other rather than running the other party off the sidewalk